up:: 061e MOC Teorias Econômicas

Teoria da descoberta científica de Smith: Espanto, Surpresa, Admiração

“Wonder, Surprise and Admiration, are words which, though often confounded, denote, in our language, sentiments that are indeed allied, but that are in some respects different also, and distinct from one another. What is new and singular, excites that sentiment which, in strict propriety, is called Wonder[;] what is unexpected, Surprise; and what is great or beautiful, Admiration” (Introdução de History of Astronomy, Adam Smith)

A observação científica vem desses sentimentos (de acordo com Smith). Fenômenos novos e singulares causam a surpresa do observador:

“We are surprised at those things which we have seen often, but which we least of all expected to meet with in the place where we find them…” (Ibid.)

Tida a surpresa, há uma preocupação surgida com o fenômeno, uma intranquilidade na mente, que buscará uma explicação ao fenômeno. Isso é espanto:

“We wonder at all extraordinary and uncommon objects, at all the rarer phenomena of nature, at meteors, comets (…), and at every thing, in short, with which we have before been either little or not at all acquainted; and we still wonder though forewarned of what we are to see.” (Ibid.)

O reestabelecimento da tranquilidade da mente vem através de explicações mentais (ideais), as quais busquem integrar tais fenômenos aparentemente díspares em um todo coeso (mesmo que ideal). O sistema novo, que explica os fenômenos que antes causavam espanto, causam agora admiração, não num sentido de novidade, mas num sentido de estar-já-explicado:

“We admire the beauty of a plain or the greatness of a mountain, though we have seen both often before, and though nothing appears to us in either, but what we had expected with certainty to see.” (Ibid.)

Influências em Smith

Problema da Indução: não se pode concluir a veracidade absoluta de uma lei geral através da observação (que sempre trata de particulares).

Método newtoniano: os fenômenos aparentes1 são caóticos, aos quais princípios são criados mentalmente para estabelecer alguma ordem a eles — estabelecer uma ordem no intelecto, não pretendendo dizer que tal ordem é real.

Ou seja, a observação de fenômenos no mundo real justifica a proposição de princípios teóricos, e tais fenômenos têm de ser formuladas de forma a que possam prever não só estes observados, mas também outros fenômenos — ou seja, faz com que tais observações “tornem-se” (possam ser vistos como) consequências necessárias.

- N’A Riqueza das Nações, Smith toma a propensão à troca como um princípio (aduzido da realidade observada em geral da troca entre seres humanos), que busca explicar a Divisão Social do Trabalho como resultado necessário

- Não coloca a explicação deste princípio como objetivo dessa obra (RN); é tomada como postulado/axioma.

Uma das premissas que Smith assume em sua obra é a de indivíduos autointeressados: não só por egoísmo, mas por um conjunto de paixões egoístas/altruístas (continuidade com seu professor, Francis Hutcheson, que assume legado intelectual de Locke).

Hume propõe o sentimento de simpatia como uma forma de autorregulação das ações morais; Smith retoma esse tema n’A Teoria dos Sentimentos Morais. Busca-se agir de forma a se colocar “em posição de honra” com relação aos demais, ou de não colocar-se contra sua simpatia.

Sobre a não-contradição entre RN e TSM

“Teoria dos sentimentos morais” propõe o homem ético, dotado de simpatia; Riqueza das Nações propõe o homem autointeressado. A distinção ocorre devido à diferença entre a motivação de um ato e suas consequências. Não me importa se o padeiro está agindo em prol de seu lucro; me importa que ele esteja produzindo algo que me interessa.

Riqueza das Nações

Centralidade do tema de valor e distribuição da renda/rendimentos.

Discutindo valor, surge questão de suas componentes (distribuição): Salário, Lucro e Renda da Terra.

Livro I

Cap. 1

Divisão Social do Trabalho como aumentador da força produtiva do trabalho. Há mais possibilidades de divisão do trabalho na Manufatura do que na agricultura, pelo fator sazonal desta

última.

Fatores para maior capacidade de trabalho por divisão do trabalho:

- Maior destreza do trabalho especializado

- Economia de tempo gasto ao se passar de um trabalho ao outro

- Invenção de máquinas

Há um aumento da riqueza, decorrente à divisão do trabalho, assim como melhores atendimentos de necessidades até mesmo dos mais simples operários (claro).

“and yet it may be true, perhaps, that the accommodation of an European prince does not always so much exceed that of an industrious and frugal peasant, as the accommodation of the latter exceeds that of many an African king, the absolute master of the lives and liberties of ten thousand naked savages” (Cap. 1, Livro I)

Hmph. Perhaps.

Cap. 2

Para Smith, tal divisão do trabalho é um produto não intencional, algo que não ocorreu de forma previamente idealizada antes de efetivar-se. É algo espontâneo.

O fundamento da divisão do trabalho, diz Smith, é a propensão humana para as trocas.

“This division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual, consequence of a certain propensity in human nature which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” (Cap. 2, Livro I)

O que motiva as trocas de mercado é o autointeresse dos homens, cada um visando-o a si próprio.

Cap. 3

Os fatores que limitam a divisão do trabalho são:

- O tamanho do mercado / a possibilidade de trocar o excedente do trabalho (cf. Brasil recém-República)

- Presença de meios de transporte acessíveis

Cap. 4: Origem e uso do dinheiro, e paradoxo do valor

A sociedade em que indivíduos contam com a divisão do trabalho para satisfação de várias de suas necessidades pode ser vista como uma “sociedade de comerciantes”.

Dinheiro surge como forma de uniformizar possibilidade de troca: sem dinheiro, troca somente ocorre quando há “coincidência de necessidades e interesses” (sem pensar na substância em comum de ambos).

Com o tempo, esse meio de troca toma a forma de metais, mais resistentes e subdivisíveis.

Smith destaca que “valor” possui dois significantes: Valor de Uso e Valor de Troca. Contraposição água (alto valor de uso, baixo valor de troca) vs diamante (baixo valor de uso, alto valor de troca).

O foco do estudo da troca tem como foco o valor de troca; como medi-lo? (Mistificação com o preço real.)

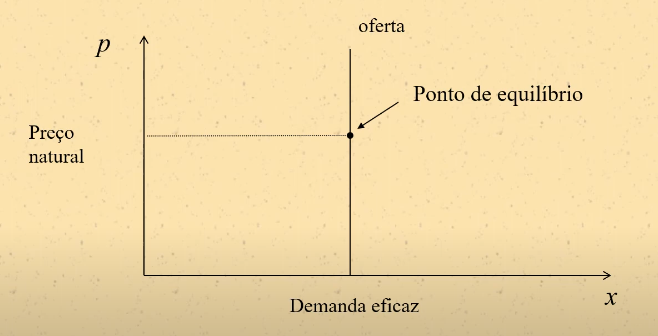

Diferencia dois conceitos: preço natural e preço de mercado. Preços de mercado orbitam em torno dos preços naturais.

Cap. 5: Trabalho e preços

- Preço real é associado ao valor da mercadoria

- O trabalho é a medida real do valor de troca das mercadorias

- O trabalho pode ser usado como medida do valor de troca de uma mercadoria:

The value of any commodity, therefore, to the person who possesses it, and who means not to use or consume it himself, but to exchange it for other commodities, is equal to the quantity of labour which it enables him to purchase or command. Labour, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities. Cap. 5, Livro I; grifo meu)

Smith vê o preço real de um bem como o “incômodo” [“toil and trouble”] requerido para sua aquisição.

“The real price of every thing, what every thing really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it. What every thing is really worth to the man who has acquired it, and who wants to dispose of it or exchange it for something else, is the toil and trouble which it can save to himself, and which it can impose upon other people.” (Ibid.)

O dinheiro concede poder, mas poder mediado:

“The power which that possession [wealth] immediately and directly conveys to him, is the power of purchasing: a certain command over all the labour, or over all the produce of labour which is then in the market. His fortune is greater or less, precisely in proportion to the extent of his power; or to the quantity either of other men’s labour, or, what is the same thing, of the produce of other men’s labour, which it enables him to purchase or command. The exchangeable value of every thing must always be precisely equal to the extent of this power which it conveys to its owner.” (Ibid.)

A medida do trabalho apresenta certas dificuldades práticas: deve levar em conta não só o tempo gasto, mas também tomando em conta as diferentes qualidades do trabalho despendido, assim como seu grau de dificuldade. Além disso, não se troca (em geral) mercadoria por trabalho, e sim mercadoria por mercadoria, ou mercadoria-dinheiro-mercadoria (Ciclo M─D─M).

“…when barter ceases, and money has become the common instrument of commerce, every particular commodity is more frequently exchanged for money than for any other commodity. The butcher seldom carries his beef or his mutton to the baker, or the brewer, in order to exchange them for bread or for beer; but he carries them to the market, where he exchanges them for money, and afterwards exchanges that money for bread and for beer. The quantity of money which he gets for them regulates too the quantity of bread and beer which he can afterwards purchase. It is more natural and obvious to him, therefore, to estimate their value by the quantity of money, the commodity for which he immediately exchanges them, than by that of bread and beer, the commodities for which he can exchange them only by the intervention of another commodity; and rather to say that his butcher’s meat is worth threepence or fourpence a pound, than that it is worth three or four pounds of bread, or three or four quarts of small beer.” (Ibid.)

Os metais, que representam o dinheiro, têm, porém, também seu valor variável, portanto tornando os valores monetários dos bens de mercado também variáveis — “[depending] always upon the fertility or barrenness of the mines which happen to be known about the time when such exchanges are made”.

O dinheiro mede, portanto, apenas o valor nominal das coisas. Seu preço real varia em quantidades de trabalho, e o valor do trabalho não varia (segundo Smith).

“Equal quantities of labour, at all times and places, may be said to be of equal value to the labourer. In his ordinary state of health, strength and spirits; in the ordinary degree of his skill and dexterity, he must always lay down the same portion of his ease, his liberty, and his happiness. The price which he pays must always be the same, whatever may be the quantity of goods which he receives in return for it. Of these, indeed, it may sometimes purchase a greater and sometimes a smaller quantity; but it is their value which varies, not that of the labour which purchases them. At all times and places that is dear which it is difficult to come at, or which it costs much labour to acquire; and that cheap which is to be had easily, or with very little labour.”

Porém Smith logo adiciona:

“But though equal quantities of labour are always of equal value to the labourer, yet to the person who employs him they appear sometimes to be of greater and sometimes of smaller value. He purchases them sometimes with a greater and sometimes with a smaller quantity of goods, and to him the price of labour seems to vary like that of all other things. It appears to him dear in the one case, and cheap in the other. In reality, however, it is the goods which are cheap in the one case, and dear in the other.

In this popular sense, therefore, labour, like commodities, may be said to have a real and a nominal price. Its real price may be said to consist in the quantity of the necessaries and conveniences of life which are given for it; its nominal price, in the [respective] quantity of money. The labourer is rich or poor, is well or ill rewarded, in proportion to the real, not to the nominal price of his labour.” (Ibid.; grifo meu)

Cap. 6: Decomposição do preço das mercadorias

Caso o trabalhador produza algo por si próprio, os frutos deste trabalho pertencem somente a si.

Caso algum indivíduo “comande trabalho alheio”, surge agora uma repartição do excedente produzido: salário aos trabalhadores, lucro ao “patrão”. Portanto, o valor da mercadoria não é regulado meramente pelo trabalho incorporado.

“As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce. The wood of the forest, the grass of the field, and all the natural fruits of the earth, which, when land was in common, cost the labourer only the trouble of gathering them, come, even to him, to have an additional price fixed upon them. He must then pay for the licence to gather them; and must give up to the landlord a portion of what his labour either collects or produces. This portion, or, what comes to the same thing, the price of this portion, constitutes the rent of land…” (Cap. 6, Livro I)

O valor de uma mercadoria, portanto, é

Salários , lucro e renda da terra .

“Whoever derives his revenue from a fund which is his own, must draw it either from his labour, from his stock, or from his land. The revenue derived from labour is called wages. That derived from stock, by the person who manages or employs it, is called profit. That derived from it by the person who does not employ it himself, but lends it to another, is called the interest or the use of money. It is the compensation which the borrower pays to the lender, for the profit which he has an opportunity of making by the use of the money. Part of that profit naturally belongs to the borrower, who runs the risk and takes the trouble of employing it; and part to the lender, who affords him the opportunity of making this profit. (…) The revenue which proceeds altogether from land, is called rent, and belongs to the landlord.” (Ibid.; grifo meu)

Juros, por exemplo, advêm do empréstimo de capital a alguém: fazem parte, portanto, do lucro do emprestador.

Cap. 7: Preço natural e preço de mercado

Preço natural é o conceito mais fundamental.

“The actual price at which any commodity is commonly sold is called its market price. It may either be above, or below, or exactly the same with its natural price.” (Cap. 7, Livro I)

Dado que o valor de toda mercadoria depende do salário, lucro e renda da terra necessários à sua produção, o seu preço natural dependerá das taxas naturais de salário, lucro e renda da terra.

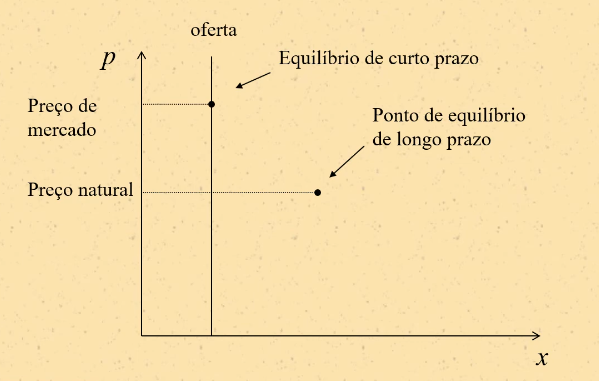

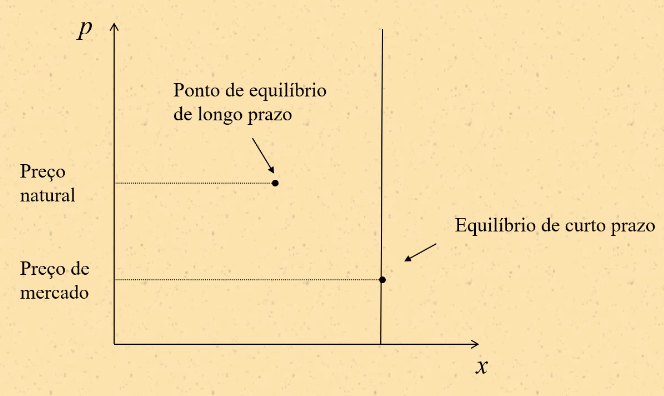

No curto prazo, preços de mercado oscilam em torno do preço natural; no longo prazo, tenderá ao preço natural, pois as taxas subjacentes tenderão a suas respectivas taxas naturais. Ou seja, o preço de mercado pode ser igual ao preço natural, a curto prazo, por pura contingência, por supercompensação de uma (ou mais) taxa(s) pela subcompensação de outra etc.

Smith distingue entre demanda eficaz [effectual demand] e demanda absoluta [absolute demand].

“…the demand of those who are willing to pay the natural price of the commodity, or the whole value of the rent, labour, and profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither (…) may be called the effectual demanders, and their demand the effectual demand; since it may be sufficient to effectuate the bringing ot the commodity to market.” (Ibid.; grifo meu)

Fonte: Valor e mercado em Adam Smith. - Ricardo Luís Chaves Feijó (FEA-RP)

(Pressupondo Bens Ordinários.)

O desvio do preço natural indica uma sobre/subcompensação de alguma das taxas subjacentes, e isso aponta para a convergência à taxa natural a longo prazo:

“If at any time it exceeds the effectual demand, some of the componentWhen it exceeds that demand, some of the component parts of its price are below their natural rate; parts of its price must be paid below their natural rate. If it is rent, the interest of the landlords will immediately prompt them to withdraw a part of their land; and if it is wages or profit, the interest of the labourers in the one case, and of their employers in the other, will prompt them to withdraw a part of their labour or stock from this employment. The quantity brought to market will soon be no more than sufficient to supply the effectual demand. All the different parts of its price will rise to their natural rate, and the whole price to its natural price.” (Ibid.)

(Há uma noção de Lei de Tendência? É similar à noção de “diagrama de corpo livre” em Física, força resultante etc.)

(Aqui supõe-se que os trabalhadores possuem real poder de poder “retirar-se” caso seu salário esteja subcompensado… Ao menos ele adiciona: “This at least would be the case where there was perfect liberty.” — Há maiores investigações no capítulo seguinte, VIII)

Sobre Monopólio e Mercados Perfeitamente Competitivos:

“A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company, has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly under-stocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate.

The price of monopoly is upon every occasion the highest which can be got. The natural price, or the price of free competition, on the contrary, is the lowest which can be taken, not upon every occasion indeed, but for any considerable time together. The one is upon every occasion the highest which can be squeezed out of the buyers, or which, it is supposed, they will consent to give: The other is the lowest which the sellers can commonly afford to take, and at the same time continue their business.” (Ibid.; grifo meu)

Cap. 8: Salários

“The produce of labour constitutes the natural recompence or wages of labour.” (Numa sociedade primitiva; Cap. 8, Livro I; grifo meu)

“What are the common wages of labour, depends every where upon the contract usually made between those two parties, whose interests are by no means the same. The workmen desire to get as much, the masters to give as little as possible. The former are disposed to combine in order to raise, the latter in order to lower the wages of labour.” (Ibid.)

É da appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock que advém a subjugação do trabalhador livre:

“As soon as land becomes private property, the landlord demands arent being the first deduction, share of almost all the produce which the labourer can either raise, or collect from it. His rent makes the first deduction from the produce of the labour which is employed upon land.” (Ibid.)

Numa sociedade “evoluída”, i.e. “comercial”, há um jogo de forças entre trabalhadores e patrões.

Os patrões possuem vantagem nas negociações de salários, pois:

“A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, or merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long-run the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him; but the necessity is not so immediate.”

Há, porém, um piso empírico aos salários:

“But though in disputes with their workmen, masters must generallyBut masters cannot reduce wages below a certain rate, have the advantage, there is however a certain rate below which it seems impossible to reduce, for any considerable time, the ordinary wages even of the lowest species of labour.

A man must always live by his work, and his wages must at least benamely, subsistence for a man and something over for a family sufficient to maintain him. They must even upon most occasions be somewhat more; otherwise it would be impossible for him to bring up a family, and the race of such workmen could not last beyond the first generation.”

O salário natural, dado pela demanda natural por trabalho, só pode crescer junto do aumento dos fundos destinado a salários:

“The demand for those who live by wages, it is evident, cannot increase but in proportion to the increase of the funds which are destined for the payment of wages.”

Como esses fundos advêm de excedentes, e excedentes somente aumentam com o crescimento econômico, conclui-se que:

“The demand for those who live by wages, therefore, necessarily increases with the increase of the revenue and stock of every country, and cannot possibly increase without it. The increase of revenue and stock is the increase of national wealth. The demand for those who live by wages, therefore, naturally increases with the increase of national wealth, and cannot possibly increase without it.”

Não nos países mais ricos, mas nos países em crescimento mais rápido. Trata-se, portanto, de demandas aceleradas por trabalho.

Com o aumento do salário, há a possibilidade de manter maiores famílias; portanto, pode-se (diz Smith) medir o aumento de salários pelo crescimento populacional.

- Em países pobres há fecundidade maior, mas também há maior mortalidade;

- Salários não são freio de taxa de nascimento, mas, a longo prazo, são um limite à população trabalhadora (pela mortalidade devida às baixas rendas)

- Dessa forma, há uma “regulação” entre a reprodução dos trabalhadores e os salários reais; no longo prazo, o salário natural tende àquele que permite a reprodução necessária da quantidade de trabalhadores minimamente necessários

- Isso dito em casos extremos: em casos que os salários estão bem acima do nível de subsistência (países relativamente ricos), não há tal relação tão explícita

Há um eco à Teoria do Salário Eficiência:

“The liberal reward of labour, as it encourages the propagation [i.e. reproduction], so it increases the industry of the common people. The wages of labour are the encouragement of industry, which, like every other human quality, improves in proportion to the encouragement it receives. A plentiful subsistence increases the bodily strength of the labourer, and the comfortable hope of bettering his condition, and of ending his days perhaps in ease and plenty, animates him to exert that strength to the utmost. Where wages are high, accordingly, we shall always find the workmen more active, diligent, and expeditious, than where they are low” (Ibid.)

Continuação: 23/05/2025

Cap 9: Taxas de lucros

Depende do estado de progresso da sociedade — assim como salários.

“The increase of stock, which raises wages, tends to lower profit.”

Concentração de capital nas cidades aumenta salários e (portanto) reduz taxas de lucro, e mutatis mutandis para o campo.

O desenvolvimento da economia (tende a) diminuir as taxas de lucro, devido à competição de capitais. Smith destaca que há uma correlação positiva entre o movimento das taxas de lucros e o movimento das Taxas de Juros.

“It may be laid down as a maxim, that wherever a great deal can be made by the use of money, a great deal will commonly be given for the use of it; and that wherever little can be made by it, less will commonly be given for it.”

Há exceções: por exemplo, exploração econômica em colônias — associados a terras com maior fertilidade (hmm…); há também casos de salários e lucros conjuntamente baixos, p. ex. estagnação após um grande crescimento.

Os altos salários nas cidades são compensados pelas baixas de taxas de juros, no que se refere ao preço das mercadorias.

Juros são sempre proporcionais ao lucro líquido. As taxas mínimas de juros devem remunerar os riscos do emprestador, ou seja, os lucros devem estar acima desta taxa mínima. Ou seja, em países ricos/mais “certos”, juros tendem a ser mais baixos; mutatis mutandis para países pobres.

Cap. 11: Renda da terra

“RENT, considered as the price paid for the use of land, is naturally the highest which the tenant can afford to pay in the actual circumstances of the land. In adjusting the terms of the lease, the landlord endeavours to leave him no greater share of the produce than what is sufficient to keep up the stock from which he furnishes the seed, pays the labour, and purchases and maintains the cattle and other instruments of husbandry, together with the ordinary profits of farming stock in the neighbourhood. This is evidently the smallest share with which the tenant can content himself without being a loser, and the landlord seldom means to leave hiim any more. Whatever part of the produce, or, what is the same thing, whatever part of its price, is over and above this share, he naturally endeavours to reserve for himself as the rent of his land, which is evidently the highest the tenant can affordr to pay in the actual circumstances of the land.”

Dado um preço (de produção?) cobrado, e descontados os salários e os lucros , o que sobra é a renda da terra .

A renda da terra é um preço de Monopólio.

“The rent of land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.”

Caso haja venda para demanda eficaz ao preço natural ,

( reposição de valor do capital.)

Há uma inconsistência: enquanto a renda da terra depende dos preços (é um “restante” das remunerações advindas do preço de venda), ela também descreve os preços, por ser uma parcela componente sua.

A renda aumenta com sua proximidade das cidades, assim como com sua fertilidade; a melhoria dos transportes também afeta a renda da terra (uniformiza os preços). O tipo de atividade que é feita nestas terras também influencia a renda da terra (justamente porque ela é composta pelo excedente da produção).

Prioritariamente a terra é usada para alimentos; satisfeito isso, para vestuário e moradia.

A renda depende da dinâmica demanda-oferta: caso haja excesso de demanda pelos produtos da terra, sua renda aumentará; caso haja um excesso de oferta destes produtos (alta concorrência, p. ex.), poderá não restar renda alguma.

Livro II

Cap. 1: Capital Circulante vs Capital Fixo

“There are two different ways in which a capital may be employed so as to yield a revenue or profit to its employer.

First, it may be employed in raising, manufacturing, or purchasing goods, and selling them again with a profit. The capital employed in this manner yields no revenue or profit to its employer, while it either remains in his possession, or continues in the same shape. The goods of the merchant yield him no revenue or profit till he sells them for money, and the money yields him as little till it is again exchanged for goods. His capital is continually going from him in one shape, and returning to him in another, and it is only by means of such circulation, or successive exchanges, that it can yield him any profit. Such capitals, therefore, may very properly be called circulating capitals.

Secondly, it may be employed in the improvement of land, in the purchase of useful machines and instruments of trade, or in such-like things as yield a revenue or profit without changing masters, or circulating any further. Such capitals, therefore, may very properly be called fixed capitals.” (grifo meu)

Capital fixo: se decompõe pouco, durável.

Capital circulante: se realiza totalmente em sua venda.

Cap. 2: Papel da moeda e crédito na circulação de mercadorias & acumulação de capital

Leitura extremamente interessante!! Ver algum dia!!

Cap. 3: Trabalho produtivo

“THERE is one sort of labour which adds to the value of the subject upon which it is bestowed: there is another which has no such effect. The former, as it produces a value, may be called productive; the latter, unproductive labour. Thus the labour of a manufacturer adds, generally, to the value of the materials which he works upon, that of his own maintenance, and of his master’s profit. The labour of a menial servant, on the contrary, adds to the value of nothing. Though the manufacturer has his wages advanced to him by his master, he, in reality, costs him no expence, the value of those wages being generally restored, together with a profit, in the improved value of the subject upon which his labour is bestowed. But the maintenance of a menial servant never is restored. A man grows rich by employing a multitude of manufacturers: he grows poor, by maintaining a multitude of menial servants. (etc)” (grifo meu)

Já existe um apontamento de Valor da Força de Trabalho e Mais-Valor, e de que o trabalho deve repor o valor da força de trabalho em seu uso.

Cap. 4: Teoria de juros

Cap. 5: Produtividade do capital em diferentes setores

Livro III

Livro IV: Os sistemas de economia política

Cap. 1: “Do princípio do sistema comercial ou mercantil”

Crítica ao Mercantilismo, estereotipado como dizendo que o dinheiro representa a riqueza. Smith destaca que a verdadeira riqueza de uma nação é a quantidade de bens que possui.

A vantagem do comércio internacional não se trata da acumulação de ouro e prata do resto do mundo, como se fazê-lo fosse, por si só, uma forma de aumentar a riqueza do país; a vantagem é justamente de vender produção excedente no mercado interno para o exterior.

Cap. 2: “Das restrições à importação dos países estrangeiros daqueles bens que podem ser produzidos internamente”

- Taxas/restrições à importação cria um monopólio no mercado interno

- Desvia-se capital e trabalho para esta atividade favorecida mais do que o normal

- Não há atividade direcionada pelo autointeresse

- Quando o preço interno é maior que o externo, há uma alocação ineficiente da sociedade, em uma área em que ela não é vantajosa (comparativamente, em particular, ao mercado externo)!

É aqui que aparece a citação da mão invisível!!

“As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.”

Aqui há uma forma em que o próprio sistema conduz a ação do indivíduo, possui força causal — logo, de acordo com Bhaskar, é algo real!

Capítulo 9: Crítica aos fisiocratas (Quesnay)

References

- História do Pensamento Econômico I - Ricardo Luís Chaves Feijó (FEA-RP)

- An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Cannan ed.), in 2 vols. | Online Library of Liberty

- The Theory of Moral Sentiments and on the Origins of Languages (Stewart ed.) | Online Library of Liberty

- The History of Astronomy (Adam Smith)