up:: 061e MOC Teorias Econômicas

related:: Questões P1 Macroeconomia B 1.2025

Fonte: SNOWDON & VANE, p. 224.

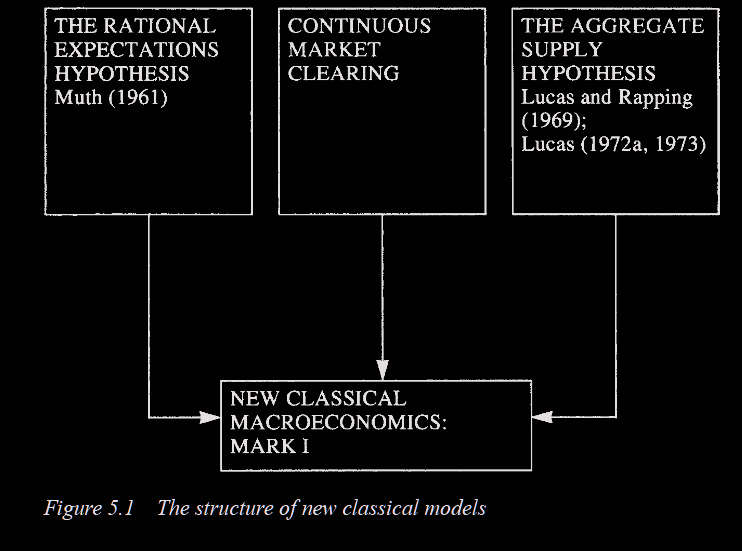

“The new classical approach as it evolved in the early 1970s exhibited several important features:

- a strong emphasis on underpinning macroeconomic theorizing with neo-classical choice-theoretic microfoundations within a Walrasian general equilibrium framework;

- the adoption of the key neoclassical assumption that all economic agents are rational; that is, agents are continuous optimizers subject to the constraints that they face, firms maximize profits and labour and households maximize utility;

- agents do not suffer from money illusion and therefore only real magnitudes (relative prices) matter for optimizing decisions;

- complete and continuous wage and price flexibility ensure that markets continuously clear as agents exhaust all mutually beneficial gains from trade, leaving no unexploited profitable opportunities.

Given these assumptions, changes in the quantity of money should be neutral and real magnitudes will be independent of nominal magnitudes.” (Snowdon and Vane, 2005, p. 243; grifo meu)

Microfundamentos Neoclássicos: Agentes Econômicos Racionais

O principal foco dos neoclássicos foi de fundamentar as análises macroeconômicas com microfundamentos neoclássicos, ou seja, baseada em agentes econômicos otimizadores1 e nos consequentes equilíbrios walrasianos.

Não-Ilusão Monetária

Assume-se que, pela racionalidade dos agentes, não há Ilusão Monetária: somente quantidades reais afetam suas tomadas de decisão (p. ex. salário real & Taxa Real de Juros).

Market Clearing contínuo

“A second key assumption in new classical models is that all markets in the economy continuously clear, in line with the Walrasian tradition. At each point of time all observed outcomes are viewed as ‘market-clearing’, and are the result of the optimal demand and supply responses of economic agents to their perceptions of prices. As a result the economy is viewed as being in a continuous state of (short- and long-run) equilibrium.” (Ibid., p. 230)

Como as tomadas de decisão são racionais (no esquema neoclássico), deve-se assumir também (ceteris paribus) que o mercado está em contínuo market clearing (“no dollar bills left on the sidewalk2”).

In market-clearing models economic agents (workers, consumers and firms) are ‘price takers’; that is, they take the market price as given and have no market power that could be used to influence price. Firms are operating within a market structure known as ‘perfect competition’. In such a market structure firms can only decide on their optimal (profit-maximizing) output (determined where marginal revenue = marginal cost) given the market-determined price. In the absence of externalities the competitive equilibrium, with market prices determined by the forces of demand and supply, is Pareto optimal and leads to the maximization of total surplus (the sum of producer and consumer surplus). (Ibid., p. 231)

Nesse sentido, assume-se não só market clearing do mercado de bens, como também do mercado de trabalho — ou seja, assume-se que todo Desemprego é Desemprego Voluntário.

Informação Imperfeita e Expectativas Racionais

Porém, como Friedman e os monetaristas trouxeram à baila, pode haver Não-Neutralidade da Moeda (i.e. fenômenos monetários afetaram o mercado real) (ao menos a curto prazo). A forma com que Lucas abordou isso foi a adoção de Informação Imperfeita pelos agentes econômicos.3

Ou seja, há uma tomada de decisões racionais dentro das informações assumidas pelos agentes econômicos: eles fazem o melhor que podem com o máximo de informação que têm às mãos. Possuem o que se chama de Expectativas Racionais’:

Ou seja, suas expectativas de inflação são formadas a partir das informações que possuem.

Dessa forma, pode ocorrer que os agentes econômicos percebam a variação do nível geral de preços (Inflação, efeito nominal) como sendo uma variação de preços relativos (em seu próprio setor de mercado), vendo-o como um sinal de mercado (fenômeno “real”) e agindo de acordo a curto prazo, até que percebam-no e reajustem suas expectativas (e sua produção)4.

Proposição de ineficácia de políticas monetárias (antecipadas)

Conforme reajustem suas expectativas, o produto e emprego voltariam ao seu equilíbrio (natural) de longo prazo (Ibid., p. 244). Ou seja, somente surpresas monetárias (não-antecipadas) afetam variáveis reais no curto prazo; caso seja uma mudança monetária antecipada, somente haverá mudança do nível de preço (nominal), não de Produto Agregado nem de emprego (real) — ou seja, há Neutralidade da Moeda.

Há uma relação sutil com a análise que Monetaristas fizeram sobre isso:

“[According to the adaptive expectations hypothesis], expectations of inflation are based solely on past actual inflation rates. The existence of a gap in time between an increase in the actual rate of inflation and an increase in the expected rate [of inflation] permits a temporary reduction in unemployment below the natural rate. Once inflation is fully anticipated, the economy returns to its natural rate of unemployment but with a higher equilibrium rate of wage and price inflation equal to the rate of monetary growth. (…) if expectations are formed according to the rational expectations hypothesis and economic agents have access to the same information as the authorities, then the expected rate of inflation will rise immediately in response to an increased rate of monetary expansion. In the case where there was no lag between an increase in the actual and expected rate of inflation the authorities would be powerless to influence output and employment even in the short run.”(Ibid., p. 181)

Ou seja, quando os agentes econômicos conhecem as regras de políticas monetárias, eles reagirão a seus efeitos e adaptarão suas produções etc., rendendo-as inócuas.5

Questões de Políticas Monetárias

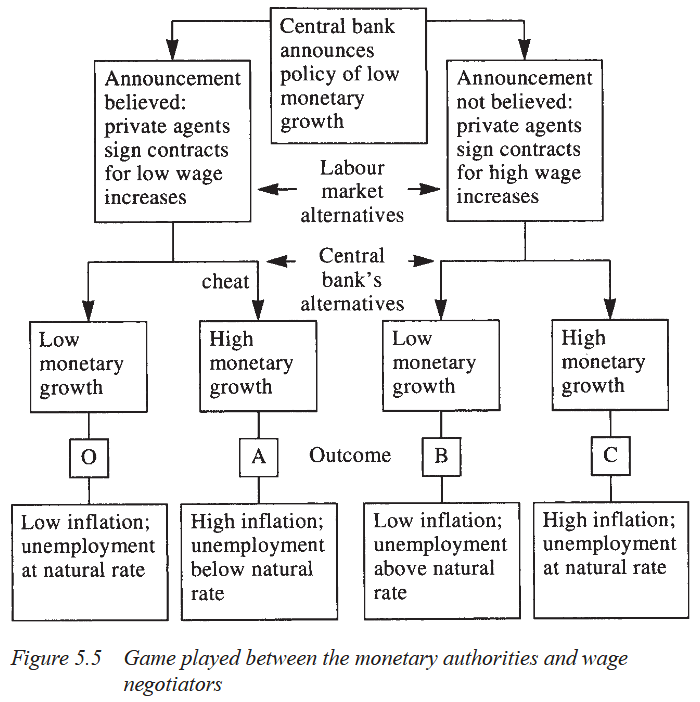

Inconsistência temporal

Políticas discricionárias de autoridades monetárias possuem viés inflacionário: há um “incentive to cheat” das autoridades quanto aos agentes econômicos, de obter um nível de welfare maior do que o dos agentes. (?)

Ou seja, ações ótimas das autoridades monetárias hoje podem não sê-lo no futuro, devido às adaptações correspondentes dos agentes econômicos (i.e. são inconsistentes temporalmente) — hence their incentive to cheat. Porém, caso acabem por “trapacear”, alterando a direção das políticas monetárias com o tempo, essa inconsistência afetará sua “reputação” para com os agentes econômicos, minando a confiança destes e afetando expectativas de inflação.

Fonte: SNOWDON & VANE, p. 255.

É neste sentido que estabelece-se que o estabelecimento de regras não-contingentes que as autoridades monetárias comprometem-se a respeitar — independentemente de que suas políticas tornem-se sub-ótimas com o tempo — são preferíveis socialmente, evitando Coordination Failure.

Independência do Banco Central

Dessa forma, advoga-se (não unanimemente) a criação de uma instituição independente, apolítica6, “whose discretion is constrained by explicit anti-inflation objectives acting as a pre-commitment device” (Ibid., p. 258) (ou seja, evitando os perigos de desconfiança que a discricionariedade confere às autoridades monetárias).

Sua independência divide-se entre

- independência de objetivos, i.e. independência política

- independência instrumental, ou seja, acesso a Políticas Monetárias

Bancos centrais podem possuir independência instrumental, mas não independência de objetivos, os quais podem ser estabelecidos politicamente.

Crítica de Lucas

References

- SNOWDON, Brian; VANE, Howard R. Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origins, Development and Current State. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005.

Footnotes

-

Com Preferências Racionais, e maximizadores de Utilidade (consumidores) e Lucro (firmas). ↩

-

BARRO apud SNOWDON & VANE, p. 231. ↩

-

Lucas’s monetary equilibrium business cycle theory (MEBCT) incorporates Muth’s (1961) rational expectations hypothesis, Friedman’s (1968a) natural rate hypothesis, and Walrasian general equilibrium methodology. With continuous market clearing due to complete wage and price flexibility the fluctuations in the MEBCT are described as competitive equilibria. But how can monetary disturbances create fluctuations in such a world? In the stylized classical model where agents have perfect information, changes in the money supply should be strictly neutral, that is, have no impact on real variables such as real GDP and employment. However, the leading and procyclical behaviour of money observed empirically by researchers such as Friedman and Schwartz (1963), and more recently by Romer and Romer (1989), suggests that money is non-neutral (ignoring the possibility of reverse causation). The intellectual challenge facing Lucas was to account for the non-neutrality of money in a world inhabited by rational profit maximizing agents and where all markets continuously clear. His main innovation was to extend the classical model so as to allow agents to have ‘imperfect information’. (Ibid., p. 238) ↩

-

“The hypothesis that aggregate supply depends upon relative prices is central to the new classical explanation of fluctuations in output and employment. In new classical analysis, unanticipated aggregate demand shocks (resulting mainly from unanticipated changes in the money supply) which affect the whole economy cause errors in (rationally formed) price expectations and result in output and employment deviating from their long-run (full information) equilibrium (natural) levels. (…) Consider, for example, an economy which is initially in a position where output and employment are at their natural levels. Suppose an unanticipated monetary disturbance occurs which leads to an increase in the general price level, and hence individual prices, in all markets (‘islands’) throughout the economy. As noted above, firms are assumed to have information only on prices in the limited number of markets in which they trade. If individual firms interpret the increase in the price of their goods as an increase in the relative price of their output, they will react by increasing their output. (…) Both firms and workers are inclined to make expectational errors and respond positively to misperceived global price increases by increasing the supply of output andlabour, respectively. As a result[,] aggregate output and employment will rise temporarily above their natural levels. Once agents realize that there has been no change in relative prices, output and employment return to their long-run (full information) equilibrium (natural) levels.” (Ibid., pp. 238-40; grifo meu). ↩

-

É o caso, p. ex., da indexação no cenário brasileiro. ↩

-

Claro. ↩